While CBDCs hold tremendous potential in closing the financial inclusion gap in LAC, they will also encounter many roadblocks generated by cultural, social, and economic determinants. Central banks and other authorities will be tasked with no less than integrating the vulnerable and marginalized into the financial system.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) have recently taken the world by storm. As of May 2022, 34 pilot projects are underway and an additional 73 countries have expressed interest in exploring CBDCs. Currently, the question is not whether CBDCs will be issued, but when.

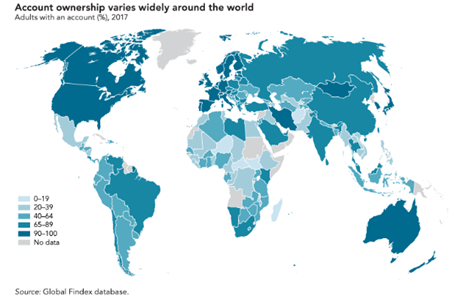

Regulators in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are showing increasing interest in CBDCs’ potential to mitigate some of the most pressing financial inclusion challenges of the region, such as high rates of unbanked people, inefficient payment systems and costly financial services. On average, as of 2017, only 52% of LAC citizens over the age of 15 have a banking account, compared to 97% in Canada and the U.S. In this regard, most economies in LAC cite financial inclusion as one of the key motivations behind their interest in CBDCs. (1) However, can CBDCs really live up to their expectations?

Adults’ bank account ownership around the world

Understanding the financial inclusion challenges in LAC

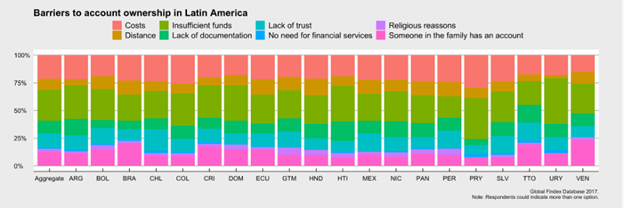

The promotion of financial inclusion requires examining the impediments to having a banking account in LAC. On average, of those adults who do not have a banking account, 32% attribute it to “insufficient funds” (i.e., minimum deposit requirements or costs of maintaining an account); 21% to financial services being too expensive; 20% to lacking the documentation to open an account; 10% to lack of trust in financial institutions; and 18% to other reasons. (2)

Technology-enabled financial innovation

Novel approaches and technologies have significantly boosted financial inclusion in LAC in the last two decades. Technology-enabled financial innovation, or fintech, is impacting the way people interact with the financial system. In LAC, mobile money has expanded dramatically over the past few years as a result of the low banking penetration and high rates of smartphone ownership (72% on average in 2020 and expected to rise to 85% by 2025). Additionally, fintech startups in LAC have recently attracted significant investments: venture capital has more than doubled every year since 2016, reaching $4 billion in 2019. As of 2021, 2,570 startups are operating in 18 countries in the region, primarily concentrated in Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia (3). Unsurprisingly, over 60% of firms are focused on payments, followed by alternative finance (lending). Further, alternative credits grew on average 147% per year between 2014 and 2020, evidencing the importance of new players in the lending space beyond incumbent banks (4).

However, despite this growth, fintechs still do not seem to be replacing commercial banks in LAC. When examining the banking status of those who borrow using mobile fintech applications in 2020, 62% of borrowers in LAC were banked relative to 30% in East Africa and 25% in South East Asia. This shows that a high share of unbanked adults does not automatically translate into a high fintech adoption rate. Additionally, for every 1000 adults, 1248 commercial bank accounts existed as of 2020, relative to only 123 mobile money accounts, suggesting that there is still considerable room for boosting financial inclusion and development through new technologies (4).

Central Bank Digital Currencies as a potential public-sector driven solution to the financial inclusion gap in LAC

CBDCs constitute a new form of money, issued digitally by a country’s central bank. And just like cash, CBDCs are intended to serve as legal tender. Unlike traditional stablecoins, which are pegged to a currency like the US Dollar, CBDCs would be a direct liability of the central bank. At a time when private companies such as Tether (USDT) and Terra (TerraUSD) are struggling to maintain their 1:1 peg to the USD, a CBDC could offer the same functionality while also being reliably backed by a Central Bank (5). Importantly, while CBDCs might seem deceptively universal, they in fact encompass various possible configurations in terms of technology. For example, while most emerging economies are interested in retail CBDCs (to be used by households and individuals), most developed nations are exploring wholesale options (only to be used by authorized financial institutions). Countries in the region are also at very different stages of implementation, with the Bahamas approaching the end of their Sand Dollar pilot, and the U.S. still assessing the potential efficacy of launching their own CBDC. But beyond the various possibilities, CBDCs could bring several benefits to the region:

I. CBDCs could help overcome accessibility barriers.

CBDCs have the potential to overcome some of the challenges discussed above by providing access to free mobile wallets backed and sponsored by Central Banks, without any of the private institution’s requirements such as official government IDs or minimum balances. This has been the case with all retail CBDCs piloted in the region, including the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank’s DCash, Uruguay’s e-Peso, and the Bahamas’ Sand Dollar (6).

II. CBDCs could help promote efficiency and innovation in the payments system.

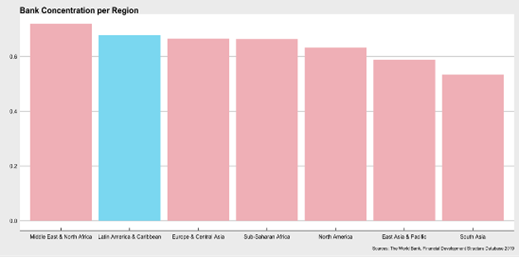

CBDCs could help promote access to safe, fast, and efficient payments systems. A CBDC would constitute the safest form of digital money, allowing for a more direct form of settlement. CBDCs could lead to a more parsimonious payments system by eliminating third-party intermediaries and replacing them with algorithmic protocols and/or governance rules to carry out reconciliation. These opportunities for CBDCs to disrupt the payments system are especially relevant in LAC, where the banking system is characterized by a high level of concentration, resulting in elevated fees, cumbersome procedures to open a bank account, and high interest rates (7).

Institutional weakness and reduced competition leaves little incentive to improve services or offer lower rates. Given CBDCs’ fungibility, they could significantly disrupt LAC’s banking sector, promoting innovation and competition, thus contributing to more accessible financial services for everyone.

III. CBDCs could make cross-border payments cheaper, faster, and more transparent.

Currently, cross-border payments are largely settled through correspondent banking arrangements that involve several parties. Domestic payments systems differ in regulatory standards and operational processes, which add frictions to payments. In this regard, the use of CBDCs for cross-border transactions could reduce these frictions in three ways: 1) Through compatibility in standards; 2) Through interlinking systems via common clearing mechanisms; and 3) By establishing a single multi-currency payments system.

The disruptive potential of CBDCs for cross-border transactions is particularly relevant in LAC, where remittances are a major source of individual financing: In 2020, remittances to LAC increased by 21.6% to 104 billion USD. Mexico, the region’s largest remittance recipient, received 42% ($52.7 billion) of the regional total. And for several smaller economies such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Jamaica, remittances as a share of GDP exceeded 20%. Despite its tremendous economic significance in LAC, average remittance fees remain high: For example, the average fee for a $200 same-day transaction is close to 8%. CBDCs would represent an incredible opportunity to improve efficiency, competition, and interoperability, ultimately reducing these costs (8).

How can the potential of CBDCs in the region be unleashed?

While the potential benefits of CBDCs are vast, their success relies on their correct implementation. These include reforms to address potential difficulties, such as low levels of financial and digital literacy and cybersecurity.

Firstly, for CBDCs to be successfully adopted, they should be either completely free (the prevailing choice) or low-cost to reach the critical mass of adults who still find financial services cost-prohibitive in LAC. Secondly, in order to prevent CBDCs from facing similar pitfalls as existing fintech alternatives, effective policies will need to address the digital infrastructure gap faced by the most vulnerable sectors. Retail CBDCs will rely on smartphones and stable internet connections, but despite the recent reduction in the digital gap catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, only 46.7% of the population in LAC have fixed broadband. Thus, CBDCs should avoid exacerbating digital inequality by introducing an unintentional layer of complexity to mobile-money usage or excluding marginalized individuals who do not yet have access to mobile phones.

While CBDCs hold tremendous potential in closing the financial inclusion gap in LAC, they will also encounter many roadblocks generated by cultural, social, and economic determinants. Central banks and other authorities will be tasked with no less than integrating the vulnerable and marginalized into the financial system. As we enter a new era in how we interact with money and payments, we have an opportunity to learn from our past mistakes and ensure that this time, no one is left out.

Sources:

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Klapper, L. F. (2012). Measuring financial inclusion: The global findex database. In Policy Research Working Paper, 6025. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank Publications.

- Barr, M. S., Harris, A., Menand, L., & Wu, W. (2020). Building the Payment System of the Future: How Central Banks Can Improve Payments to Enhance Financial Inclusion. Available at SSRN 3664790.

- Finnovista 2020. https://www.finnovista.com/en/

- Fortune. Terra USD DEI Crypto Collapse Stablecoin Dollar Peg. https://fortune.com/2022/05/19/terrausd-dei-crypto-collapse-stablecoin-dollar-peg/

- Herrera, L., Lambert, F., Ramos, G., & Torres, J. (2021). Fintech and Financial Inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean. IMF Working Papers, 2021(221).

- Calle, George, and Daniel Eidan. “Central Bank Digital Currency: an innovation in payments.” R3 White Paper, April (2020).

- Sahay, M. R., Cihak, M., N’Diaye, M. P., Barajas, M. A., Mitra, M. S., Kyobe, M. A., … & Yousefi, M. R. (2015). Financial inclusion: can it meet multiple macroeconomic goals?. International Monetary Fund.